The Canceled Swedish E-Methanol Factory may Rise from the Ashes

Last year, wind energy company Ørsted stopped plans for the green shipping fuel and E-Methanol plant FlagshipONE in Sweden. Yet, in an unexpected twist, Liquid Wind, the company that initially developed FlagshipONE, wants to build an even larger E-Methanol factory at the same location.

E-Methanol, made from carbon dioxide and clean hydrogen, is a promising climate solution for sectors where direct electrification is not viable. It could serve as a clean shipping fuel, an electricity storage solution, or a feedstock for producing chemicals and aviation fuel.

Particularly in the shipping industry, Methanol is widely perceived as a promising option for decarbonizing large container ships that cannot plausibly be electrified. Companies like Stena Line and Maersk invested in dual-fuel ships with Methanol-ready engines.

But those ideas received a major blow last year when the Danish wind energy giant Ørsted pulled the plug for FlagshipONE, a planned E-Methanol factory in Örnsköldsvik, Sweden. The project was originally planned by another company called Liquid Wind.

Liquid Wind was founded in 2017 and has its headquarters in Gothenburg, Sweden. As its name suggests, it plans to turn renewable electricity sources like wind energy into liquid Methanol. In 2020, the startup raised 2.4 million Swedish Krona (around 210,000 EUR or 220,000 USD) via crowdfunding. Its investors include, among others, Siemens Energy, the process technology supplier Tosoe, and the energy company Uniper.

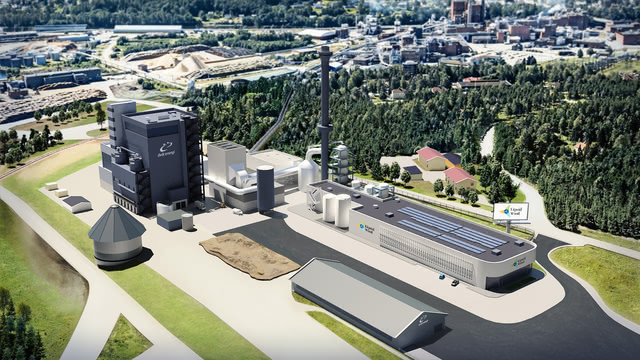

In 2020, Liquid Wind announced a partnership with Övik Energi, a company operating a biomass power plant in Örnsköldsvik, for the construction of its first E-Methanol facility, which would later be called FlagshipONE. The power plant could deliver carbon dioxide from a biogenic source, an essential consideration for any such carbon capture and utilization (CCU) project.

In early 2022, the Danish renewable energy giant Ørsted joined the project and fully acquired it later that year. Liquid Wind was no longer involved. In December 2022, Ørsted announced a "final" investment decision for FlagshipONE.

Eventually, it turned out that the decision was not so final after all. "The liquid e-fuel market in Europe is developing slower than expected, and we have taken the strategic decision to de-prioritise our efforts within the market and cease the development of FlagshipONE," Ørsted wrote in 2024. Subsequently, Ørsted canceled its contracts with the project's suppliers and Övik Energi.

A lack of offtake agreements, a less ambitious EU climate policy, and a more challenging political landscape in Sweden may have contributed to the project's eventual demise. I have covered Ørsted's cancellation of FlagshipONE last year. Yet, there was an open question I had not addressed: what happened to Liquid Wind and its other projects?

FlagshipONE failed, but what about FlagshipTWO and FlagshipTHREE?

As the name implies, FlagshipONE was the first of multiple projects. Liquid Wind is still pursuing FlagshipTWO in Sundsvall and FlagshipTHREE in Umeå, both in Sweden. Furthermore, Liquid Wind is involved as a project planner for another project in Sweden in collaboration with Uniper and has plans for more E-Methanol projects in Finland.

In an unexpected twist of events, Liquid Wind recently announced a new project in Örnsköldsvik, the location of the previously canceled FlagshipONE. Unlike the original project, which was targetting a production capacity of 50,000 tons per year, the new project should produce twice as much. Liquid Wind has certainly not given up on E-Methanol.

Yet, it raises some obvious questions. Ørsted is an established player in the energy business. Liquid Wind is a relatively small startup. Ørsted apparently did not think an E-Methanol project was viable and could not secure offtake agreements. Why would Liquid Wind believe that it can do better?

To find out, I talked to Claes Fredriksson, the CEO of Liquid Wind. Liquid Wind had identified Örnsköldsvik as a location with favorable properties for an E-Methanol plant back in 2019. "It's a good site, close to the port, close to the power plant, close to CO₂," Fredriksson told me. "We wouldn't then want to give up the idea of having a project on that site. So, as soon as we could, we went back to Övik Energi."

Ørsted's core business is offshore wind energy, and according to Fredriksson, the Danish company wanted to focus on this core business and also learned that operating an E-Methanol plant is more complicated than they first assumed. "Compared to Ørsted, we are a smaller player, but we only do Methanol. That's our bread and butter and our only focus. Therefore, we will try very hard to make it work."

In media reports after the cancellation of FlagshipONE, Ørsted representatives said that the company was unable to secure long-term offtake agreements.

"If you charge them a low enough price, there will always gonna be offtakers," Fredriksson said. "There are multiple companies out there, either traders or shipping companies, that are willing to buy an alternative shipping fuel starting from 2027." Fredriksson also told me they are in conversations with companies planning to make sustainable aviation fuels from Methanol starting in the early 2030s.

One reason why Liquid Wind hopes to offer E-Methanol at a lower price point is that it is now targetting an even larger production plant.

"Scale generally brings efficiencies up, and then the costs per unit of fuel come down," Fredriksson said in our conversation. It is something I hear a lot in conversations with people from the chemical industry. Scaling up is an important tool to bring costs per unit down.

However, larger scales also obviously require more investment and come with more risks. It is easier to iterate technology development in smaller facilities, and in the case of failed projects, larger factories obviously mean more losses. Scaling by the right amount at the right time is, therefore, one of the most crucial challenges for any industrial cleantech innovation.

Fredriksson was quite clear in our conversation that operating a plant at these scales comes with considerable challenges: "It is quite complicated. These are big plants. We deal with power in large quantities coming in, we deal with gas coming in, and we deal with fuel as an output." (One may add that capturing carbon dioxide from existing power plants is not necessarily easy either.)

All of Liquid Wind's currently planned projects have capacities between 100,000 and 130,000 tons annually, substantially more than most existing projects in this space. In Denmark, the company European Energy is building an E-Methanol plant with a capacity of 32,000 tons per year, which is currently the most advanced such project in Europe.

Two CO2-to-Methanol plants with a capacity comparable to what Liquid Wind is planning and already in operation have been built by the Icelandic company Carbon Recycling International in China. Those have, however, no integrated hydrogen electrolysis production. They utilize hydrogen from existing fossil-based industrial processes.

Some Chinese companies are targeting even larger scales. Wind energy company Goldwind has announced the groundbreaking for a 500,000-ton green Methanol plant in April 2024, producing a mixture of Bio- and E-Methanol. Car maker Geely has similarly ambitious plans.

With lower prices, Liquid Wind believes it will have no problem finding offtakers for its product, and Fredriksson told me they have non-binding offers from shipping companies for their expected price tag.

Construction in Örnsköldsvik will not start for some time, as the facility will need a new environmental permit. According to Fredriksson, that could happen within the next twelve to fifteen months, and in parallel, Liquid Wind is talking to potential investors. A final investment decision could follow in the fall of 2026.

Construction at FlagshipTHREE could start this Year

Liquid Wind's most advanced project is located around 100 kilometers northeast of Örnsköldsvik in Umeå. It is the one that was initially named FlagshipTHREE. An environmental permit was granted in January of this year.

Like in Örnsköldsvik, the project in Umeå is located close to a port and an existing power plant. The Dåva power plant burns household waste and biogenic inputs in its two blocks. Liquid Wind only wants to utilize the biogenic share of those CO₂ emissions. The power plant plans to use Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) for its remaining fossil emissions. However, that will likely not happen any time soon, as Sweden currently has no operational carbon dioxide storage sites.

"We plan to have a final investment decision, and construction start in the second half of this year," Liquid Wind's CEO said about the project in Umeå. "We have two non-binding offers for the offtake, so we are in pretty good shape on the offtake side."

Furthermore, Liquid Wind is in regular conversations with the Port of Gothenburg, which is upgrading its infrastructure for Methanol bunkering. (Bunkering is the shipping industry's term for refueling.) "As soon as we have fuel, they want to be part of it," Fredriksson said.

The Port of Gothenburg is also where the Stena Germanica, a passenger ship that runs partly on Methanol, starts its regular voyages to Kiel in Germany. Yet, these days, this Methanol fuel still mostly comes from fossil fuels.

It appears Liquid Wind is optimistic that it can kickstart a sizeable E-Methanol industry in Europe. On a personal note, after researching and writing this article, I am not sure whether what they are planning is overly ambitious and unrealistic — or whether it is exactly the kind of bold plan that is needed in times of a climate emergency.

Ørsted's decision to cancel FlagshipONE was widely seen as a disappointment in the green methanol sector. However, it has not discouraged others from pursuing these technologies.

Fossil-Free Plastics and Waste-Gasification-to-Methanol

In September 2024, A.P. Møller Holding, the company that owns a large part of Maersk's shares, launched a startup called VioNeo, which plans to build a fossil-free plastics plant based on Methanol-to-Olefins technology from Honeywell in Belgium. European Energy, the company currently building a 32,000 tons per year E-Methanol plant in Denmark, received a funding grant from the EU Innovation Fund for a larger plant with a capacity of 100,000 tons in October 2024.

In January this year, Spanish energy company Repsol announced an investment for a Waste-Gasification-to-Methanol plant named Ecoplanta. It also received support from the EU Innovation Fund. Repsol will use technology from Canadian company Enerkem.

Enerkem is one of several companies trying to make waste gasification work, a technology with a long history of failed projects. Lately, Enerkem has had its own difficulties. Its only operational plant in Edmonton, Canada, was shut down after producing far less than the initially expected amounts. Plans for multiple Enerkem projects in the Netherlands were canceled. However, with Repsol's investment and another project in Canada under construction, it appears Enerkem is still in business. (Update: According to an article by Canadian newspaper La Presse that came out shortly after this newsletter, construction on that project built by the company Recyclage Carbone Varennes is currently on hold. The company is in financial trouble and is currently unable to secure the funding necessary to finish the project.)

Of course, none of these projects have been built yet. Whether they will succeed remains to be seen. But it appears green Methanol still has momentum.

Author: Hanno Böck

Elsewhere

Speaking of Methanol, I gave a presentation at the 38th Chaos Communication Congress (38C3) in December: Is Green Methanol the missing piece for the Energy Transition? The recording is also available on YouTube.